Report | Annual Statistical Risk Assessments

Countries at Risk for Mass Killing 2023–24: Early Warning Project Statistical Risk Assessment Results

Genocide and related crimes against humanity are devastating in their scale and scope. They leave enduring scars for survivors and their families, as well as long-term trauma in societies. Moreover, the economic, political, and social costs and consequences of such crimes often extend far beyond the territory in which they were committed.

Working to prevent future genocides requires an understanding of how these events occur, including considerations about warning signs and human behaviors that make genocide and other mass atrocities possible.

We know from studying the Holocaust and other genocides that such events are never spontaneous. They are always preceded by a range of early warning signs. If warning signs are detected and their causes addressed, it may be possible to prevent catastrophic loss of life.

The Early Warning Project—a joint initiative of the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College—has produced a global risk assessment every year since 2014. Since then, we have seen multiple mass atrocities occur, including a genocide against the Rohingya in Burma, the killing of hundreds of thousands of civilians in South Sudan, and identity-based killings of civilians in Ethiopia. Even in cases like these where warnings have been issued, they have simply not prompted enough early action.

This assessment identifies the risk—the possibility—that a mass killing may take place. On average, one or two countries experience a new episode of mass killing each year. But relative infrequency does not make the brutality less devastating for victims: a mass killing, by our definition, is 1,000 or more civilians within a country deliberately killed by armed forces in the same country (whether government or nonstate), over a period of a year or less, because of their membership in a particular group. Virtually all cases of genocide include mass killings that meet this definition.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s founding charter, written by Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, mandates that our institution strive to make preventive action a routine response when warning signs appear. Wiesel wrote, “Only a conscious, concerted attempt to learn from past errors can prevent recurrence to any racial, religious, ethnic or national group. A memorial unresponsive to the future would also violate the memory of the past.”

The Museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide was established to fulfill that vision by transmitting the lessons and legacy of the Holocaust and “to alert the national conscience, influence policy makers, and stimulate worldwide action to confront and prevent genocide.” In collaboration with Dartmouth College, the Simon-Skjodt Center’s Early Warning Project works to be a trusted partner for policy makers by using innovative research to identify early warning signs. In doing so, we seek to do for today’s potential victims what was not done for the Jews of Europe.

One of the Simon-Skjodt Center’s goals is to ensure that the US government, other governments, and multilateral organizations have institutionalized structures, tools, and policies to effectively prevent and respond to genocide and other mass atrocities. The Early Warning Project is listed in the Global Fragility Act (2019) as a source to help determine where the US government should prioritize its Global Fragility Strategy, a landmark ten-year effort to improve US action to stabilize conflict-affected areas and prevent extremism and violent conflict.

The more governments and international organizations develop their own early warning tools and processes, the better our Early Warning Project can help serve as a catalyst for preventive action. For example, the US Atrocity Risk Assessment Framework, updated in 2022, sets out guidance for the kind of in-depth analysis that should be conducted on countries near the top of our Statistical Risk Assessment.

In many places, mass killings are ongoing—in countries such as Burma, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Syria. These cases are well known. But this risk assessment’s primary focus—and the gap we seek to fill—is to draw attention to countries at risk of a new outbreak of mass killing. We use this model as one input for selecting countries for more in-depth research and policy engagement. The Simon-Skjodt Center focuses on situations where there is a risk of large-scale, group-targeted, identity-based mass atrocities, or where these are ongoing, and where we believe we can make the most impact based on a combination of factors. These factors include the ability for Simon-Skjodt Center staff or partners to conduct rigorous field work in the area (or a pre-existing level of staff expertise in the area), opportunities for effective engagement with the community at risk, and the need to draw attention to cases where policy, media, and public attention on the case are lower than merited by the level of risk.

Preventing genocide is of course difficult. In deciding how to respond, policy makers face an array of constraints and competing concerns. As we confront ongoing crises, we must not neglect opportunities to prevent new mass atrocities from occurring. We know from the Holocaust what can happen when early warning signs go unheeded. We aim for this risk assessment to serve as a tool and a resource for policy makers and others interested in prevention. We hope this helps them better establish priorities and undertake the discussion and deeper analysis that can help reveal where preventive action can make the greatest impact in saving lives.

Naomi Kikoler

Director

Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide

January 2024

IntroductionBack to top

Policy makers face the challenge of simultaneously responding to ongoing mass atrocities, such as those in Burma, China, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Syria, and trying to prevent entirely new mass atrocity situations. A critical first step toward prevention is accurate and reliable assessment of countries at risk for future violence. The Early Warning Project’s Statistical Risk Assessment uses publicly available data and statistical modeling to produce a list of countries ranked by their estimated risk of experiencing a new episode, or onset, of mass killing. This report aims to help identify countries where preventive actions may be needed. Earlier identification of risk broadens the scope of possible preventive actions.

In essence, our statistical model identifies patterns in historical data to answer the following question: Which countries today look most similar to countries that experienced mass killings in the past, in the year or two before those mass killings began? The historical data include basic country characteristics, as well as data on governance, war and conflict, human rights and civil liberties, and socioeconomic factors.

This report highlights findings from our Statistical Risk Assessment for 2023–24, focusing on:

- Countries with the highest estimated risks of a new mass killing in 2023 or 2024

- Countries where estimated risk has been consistently high over multiple years

- Countries where estimated risk has increased or decreased significantly from our last assessment

- Countries with unexpected results

We recognize that this assessment is just one tool. It is meant to be a starting point for discussion and further research, not a definitive conclusion. We aim to help governments, international organizations, and nongovernmental organizations determine where to devote resources for additional analysis, policy attention, and, ultimately, preventive action. We hope that this report and our Early Warning Project as a whole inspire governments and international organizations to invest in their own early warning capabilities.

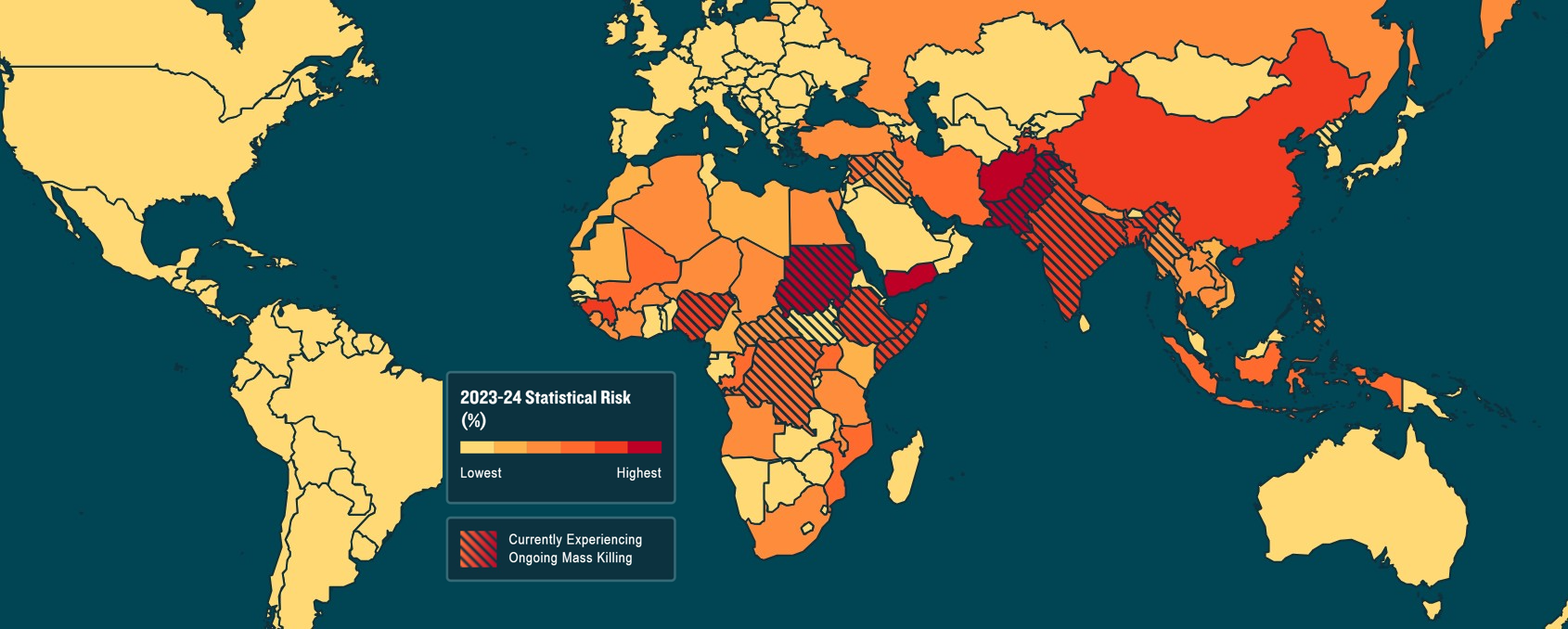

Figure 1. Heat map of estimated risk of new mass killing, 2023–24Back to top

Understanding these resultsBack to top

Before discussing the results, we underscore six points about interpreting this Statistical Risk Assessment:

First, as a statistical matter, mass killings are rare. On average, about 1.5 percent of countries see a new mass killing in any given year—that means two or three countries. Our risk model predicts a similar number of new episodes of mass killing, so the average two-year risk estimate produced by our model is about 1 percent. Out of 166 countries only Afghanistan and Pakistan have two-year risk estimates greater than 6 percent, or about a one in 16 chance of experiencing a new mass killing in 2023 or 2024.

Second, our model is designed to assess the risk of a new mass killing, not of the continuation or escalation of ongoing episodes. Much of the Simon-Skjodt Center’s work spotlights ongoing mass atrocities and urges lifesaving responses. We focus here on the risk of new mass killing to help fill an analytic gap that is critical to prevention. This feature is especially important to bear in mind when interpreting results for countries that are currently experiencing mass killings, including six in the top 15 of this assessment (see Figure 2 and our website for a full list of countries). For these countries, our assessment should be understood as an estimate of the risk that a new mass killing event would be launched by a different perpetrator or targeting a different civilian group in 2023 or 2024. (Our model estimates that having a mass killing currently in progress is associated with lower risk of another one beginning.) While it is important to focus on countries already experiencing mass killing and at high risk of a new onset, it is also essential to focus additional attention on high-risk countries with no ongoing episodes. However, regardless of their ranking in this assessment, cases of ongoing atrocities demand urgent action (see Figure 4 and our website for the Early Warning Project’s complete list of ongoing mass killings).

Third, we only forecast mass killings within countries (i.e., in which the perpetrator group and the targeted civilian group reside in the same country). This risk assessment does not forecast civilian fatalities from interstate conflict, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or when a civilian group in a country is attacked by a nonstate armed group that resides outside of the country’s borders, such as Hamas’s attack on Israeli civilians. Situations in which large numbers of civilians are killed deliberately by an armed group from another country are not captured in our historical mass killing data or current forecasts. We have chosen to focus our statistical risk assessment on the form of mass killing that has been the most common in the post-World War II era. Since 1945, foreign invasions and wars between states have been extremely rare, making statistical modeling of mass killings in those conflicts difficult. Mass killings within states have been far more common. The decision to exclude interstate mass killings from our model does not involve a value judgment about the moral or practical significance of such atrocities, only a pragmatic judgment about what we are able to forecast more reliably.

Fourth, readers should keep in mind that our model is not causal: the variables identified as predicting higher or lower risk of mass killings in a country are not necessarily the factors that drive or trigger atrocities. For example, a large population does not directly cause mass atrocities; however, countries with large populations have been more likely to experience mass killing episodes in the past, so this factor helps us identify countries at greater risk going forward. We make no effort to explain these kinds of relationships in the data, some of which can seem perplexing; we only use them for their predictive value. An important consequence of the non-causal nature of these forecasts is that actions aimed at addressing risk factors identified in the model would not necessarily be effective ways of mitigating the risk of mass atrocities; this assessment does not seek to evaluate atrocity prevention policy prescriptions. For example, although our model finds that countries that have not accepted the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights are at greater risk of experiencing mass killings than are other countries, this does not imply that action to encourage ratification of the Optional Protocol would help prevent mass killings. This assessment is meant to be a starting point for discussion and further research, pointing policy makers and other practitioners to the countries that merit additional analysis to determine how to help prevent atrocities.

Fifth, this assessment is based on available data reflecting conditions as of the end of 2022. Events that occurred in 2023, such as the outbreak of conflict in Sudan and the coups in Niger or Gabon, are not reflected in country risk estimates. Our assessment relies on publicly available data that are reliably measured for nearly all countries in the world, regularly updated, and historically available going back many years. Most of these data are published a few months after the end of the calendar year to which they refer. As a result, we are able to publish our forecasts for 2023–24, based on data on 2022, only in late 2023.

Sixth, because we revised the set of risk factors used in the model this year, users should not make direct comparisons between country risk estimates and rankings from prior years to the current assessment. Every few years, we conduct a systematic review of our Statistical Risk Assessment and consider changes to the data and model. For this year’s assessment, we added variables on women’s participation in civil society organizations, government censorship of the media, and discrimination against ethnic groups. We also added new variables in an effort to improve our forecasts for countries with ongoing mass killings. At the same time, we decided to remove data on freedom of movement because it produced large year-to-year shifts in several countries’ risk estimates that we were unable to explain. (All changes in the data are explained in the data dictionary.) Since apparent changes in a country’s risk from the 2022-23 assessment to this year reflect some combination of changes in the model and changes in the country, direct comparisons can be misleading.

Definition: mass killingBack to top

By our definition, a mass killing occurs when the deliberate actions of armed groups in a particular country (including but not limited to state security forces, rebel armies, and other militias) result in the deaths of at least 1,000 noncombatant civilians in that country over a period of one year or less. The civilians must also have been targeted for being part of a specific group. Mass killing is a subset of “mass atrocities,” which we define more generally as “large-scale, systematic violence against civilian populations.”

MethodsBack to top

To produce this assessment, we employ data and statistical methods designed to maximize the accuracy and practical utility of the results. Our model assesses the risk for onset of both state-led and nonstate-led mass killings over a two-year period.

DataBack to top

The data that inform our model come from a variety of sources. On the basis of prior empirical work and theory, we selected more than 30 variables, or risk factors, as input for our statistical model (see the discussion of our modeling approach below). All data used in our model are publicly available, regularly updated, and available without excessive delay. The data also have, in our estimation, minimal risk of retrospective coding bias (coded in a manner influenced by either the presence or absence of observed mass killings), cover all or almost all countries in the world, and go back at least to 1960 (but ideally to 1945). We include variables reflecting countries’ basic characteristics (e.g., geographic region, population); socioeconomic measures (e.g., changes in gross domestic product per capita); measures of governance (e.g., restrictions on parties); levels of human rights (e.g., freedom of discussion); and records of violent conflict (e.g., battle-related deaths, ongoing mass killings). Alongside the model, we publish a data dictionary, which includes descriptions of all the variables (also referred to as risk factors) included in our model. We also make the model and all data available on our GitHub repository. The only data set the Early Warning Project maintains is that of new and ongoing mass killing events.

Despite our efforts to include a wide range of relevant variables, data availability and quality are continuing challenges. Some risk factors that might be useful predictors (e.g., dangerous speech) are not included in the model because data meeting the above criteria are unavailable. Additionally, in situations where governments deliberately restrict access to international observers, such as in Afghanistan, Burma, Ethiopia’s Tigray or Oromia regions, or China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, existing data might not fully reflect conditions in the country.

Modeling approachBack to top

Our modeling approach is described in detail on our website. We use a logistic regression model with “elastic-net” regularization, which is one approach that aids in avoiding “overfitting” the model to the data. Based on a set of more than 30 variables and data on mass killing going back to 1960, the algorithm identifies predictive relationships in the data, resulting in an estimated model. We then apply this model to recent data (from 2022 for the 2023–24 assessment) to generate forecasts. While the exact number of countries varies by year, the project includes all internationally recognized independent states with populations of more than 500,000. The model automatically selects variables that are useful predictors; see our methodology page for a list of variables selected by the model. We emphasize that these risk factors should not be interpreted as causes or “drivers” of risk but simply as correlates of risk that have proven useful in forecasting. Indeed, many of these variables may be useful predictors not because they cause mass killing to be more likely, but because they indirectly serve as proxies for other factors that do.

AccuracyBack to top

We assessed the accuracy of this model in ways that mimicked how we use its results: We built our model on data from a period of years and then tested its accuracy on data for later years (i.e., we conducted out-of-sample testing). Our results indicate that in any given year, about two out of every three countries that later experienced a new mass killing ranked among the top-30 countries.

Highlights from the 2023–24 Statistical Risk Assessment Back to top

Our model generates a single risk estimate for each country, representing the estimated risk for a new state-led or nonstate-led mass killing. Figure 2 displays the estimated risk in 2023 or 2024 for the 30 highest-ranked countries. For every country in the top 30, we recommend that policy makers consider whether they are devoting sufficient attention to addressing the risks of mass atrocities occurring within that country. Strategies and tools to address atrocity risks should, of course, be tailored to each country’s context.

Further qualitative analysis is needed to understand the specific drivers of risk in a given situation, the mass atrocity scenarios that could be deemed plausible, and the resiliencies that could potentially be bolstered to help prevent future atrocities. This kind of deeper qualitative assessment is exemplified in Early Warning Project reports on Indonesia (2022), Côte d’Ivoire (2019), Mali (2018), Bangladesh (2017), and Zimbabwe (2016). Concerned governments and international organizations should consider conducting their own assessments of countries at risk, which should suggest where adjusting plans, budgets, programs, and diplomatic strategies might help prevent mass killings in high-risk countries. For example, the 2022 US Strategy to Anticipate, Prevent, and Respond to Atrocities outlines commitments by the US government to conduct these types of assessments on identified priority countries, guided by the US Atrocity Risk Assessment Framework. Because these qualitative assessments are resource intensive, policy makers should prioritize that type of analysis on countries whose risk estimate is relatively high, according to this Statistical Risk Assessment, and where opportunities for prevention exist.

Figure 2. Top 30 countries by estimated risk of new mass killing, 2023–24Back to top

Note: * Indicates ongoing state-led mass killings; ° indicates ongoing nonstate-led mass killings. Some countries have multiple ongoing episodes of one or both types (e.g., Burma/Myanmar has three ongoing state-led mass killings; Nigeria has an ongoing state-led and an ongoing nonstate-led mass killing). Risk-based ranking is in parentheses. The probabilities displayed here are associated with the onset of an additional mass killing episode. See the full list of ongoing mass killings on our website.

In the paragraphs below, we discuss each country’s risk according to our statistical model and note any instances of ongoing violent conflict, group-targeted human rights abuses, and significant events that pose risk for major political instability. These brief summaries include information that goes beyond the data in our statistical model, but they are not intended to provide a comprehensive analysis of factors contributing to atrocity risk. Rather, they are intended to serve as starting points for those who are interested in deeper qualitative analysis. For each country, we also identify the specific factors that account for the risk estimates from our model (see “Methods” above for more detail on the risk factors in the model) and note whether the country is experiencing an ongoing mass killing.

Key questions users should askBack to top

The results of this risk assessment should be a starting point for discussion and further analysis of opportunities for preventive action. For countries in each of the following categories, we recommend asking certain key questions to gain a fuller understanding of the risks, adequacy of policy response, and to identify additional useful lines of inquiry.

Highest-risk and consistently high-riskBack to top

- Are the risks of large-scale, systematic attacks on civilian populations in the country receiving enough attention?

- What additional analysis would help shed light on the level and nature of atrocity risk in the country?

- What kinds of crises or events (e.g., coups, elections, leadership changes, protests, etc.) might spark large-scale violence by the government or nonstate actors?

Increasing riskBack to top

- What events or changes explain the big shifts in estimated risk?

- Have there been additional events or changes, not yet reflected in the data, which are likely to further shift the risk?

- Is the increase part of an ongoing trend?

Unexpected resultsBack to top

- What accounts for the discrepancy between the statistical results and experts’ expectations?

- What additional analysis would help shed light on the level and nature of atrocity risk in the country?

Highest-risk countriesBack to top

- Afghanistan (Rank: 1): Afghanistan has ranked among the ten highest-risk countries in our assessment for multiple years. Several groups in Afghanistan face a high risk of targeted violence. The UN recorded 395 civilians killed and 1,273 civilians wounded in Afghanistan from June 15, 2022, to May 30, 2023, with reports of increased attacks on places of worship in this period. The Hazara community continues to face risk of crimes against humanity and even genocide, evidenced by a history of persecution and mounting attacks by multiple perpetrators since August 2021. In recent months, the Taliban have increased restrictions on the rights of women and girls, including bans on women attending university, working for NGOs, and accessing certain public spaces. Abuses have continued against groups perceived to oppose the Taliban. The UN reported 800 human rights abuses, including over 200 extrajudicial killings, against individuals affiliated with the former Afghan government from August 15, 2021, to June 30, 2023. Reports also indicate that the Taliban has used torture, extra judicial executions, mass arbitrary arrest and detention against civilians accused of anti-Taliban resistance in Panjshir province. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Afghanistan’s high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, that it experiences political killings that are frequently approved of or incited by top leaders of government, and the presence of battle-related deaths (primarily armed conflict between the de facto Taliban Government of Afghanistan, Islamic State [IS], and the National Resistance Front of Afghanistan).

- Pakistan (Rank: 2): Pakistan consistently ranks among the ten highest-risk countries in our assessment. Pakistan faces a number of security challenges, including attacks by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which is responsible for a nonstate-led mass killing episode that we have judged as ongoing since 2001. The political landscape has remained tumultuous in recent years. Crisis unfolded in April 2022 when former Prime Minister Imran Khan dissolved parliament and was ultimately removed from office. After authorities arrested Khan in May 2023, large scale protests across several cities resulted in thousands arrested. The ongoing uncertainty has far-reaching implications for Pakistan's political stability, which is also threatened by the country’s economic crisis. Minority religious communities, including those vulnerable under Pakistan's blasphemy laws, continue to grapple with elevated threats to their security. Christians, Hindus, Sikhs, Ahmadi Muslims, Sunni Muslims, and Shia Muslims faced targeted attacks throughout 2022, according to the US Department of State. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Pakistan’s high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, large population, and lower than average respect for religious freedom.

- Yemen (Rank: 3): Yemen has ranked among the ten highest-risk countries for multiple years. While violence has significantly decreased following a 2022 truce between the Saudi-led coalition and the rebel Houthi group, Yemen’s high risk this year suggests that the country continues to display characteristics common among countries prone to new mass killings. Parties to the conflict have not reached a peace agreement, but the UN Special Envoy for Yemen remains hopeful that one will be reached even amid continued violence against civilians violence against civilians. However, risks of expanded conflict remain, with the Houthis and Yemeni government forces reportedly “rearming and recruiting at alarming rates.” Baha'i religious minority communities face ongoing persecution by Houthi authorities. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Yemen’s high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, that it experiences political killings, and its lower than average respect for religious freedom.

Countries in the top ten that are not discussed in this year’s report are Guinea, Somalia, and Bangladesh. To learn more about the factors that contributed to the high-risk estimate of any of these countries, visit the country pages on our website and use the “select a country” dropdown in the top right corner.

Burma: The difference between new onsets and continuing mass killingBack to top

Some readers may be surprised that a country like Burma, where the scale and intensity of the war crimes and crimes against humanity are well known, does not rank among the highest-risk countries in our assessment.

Why is Burma not ranked higher in our risk assessment?

The percentage risk and ranking for each country represents the estimated probability that a new onset of mass killing begins in that country—that either a new perpetrator group emerges and kills more than 1,000 civilians of a specific group, or an existing perpetrator group begins targeting a new group of civilians—not that an existing mass killing continues. This decision follows the project’s goal to provide early warning before large-scale killings begin, while opportunities for prevention are greatest.

In Burma, there were three ongoing mass killings as of the end of 2022: a state-led mass killing against civilians suspected of opposing the military junta since 2021, a state-led mass killing against Rohingya civilians since 2016, and a state-led mass killing against ethnic minority groups—including the Karen, Kachin, Ta'ang, Mon, Lisu, and Shan—in the country’s east since 1948. Burma falls lower on our list than might be expected because of its multiple ongoing mass killings and because the target groups are so broad. Burma’s risk and ranking (2.0 percent risk and 33rd rank) are estimates of the likelihood that a different civilian group would be targeted and/or a new perpetrator group would emerge in 2023 or 2024.

See the Museum’s website for more information about the crisis in Burma, efforts to bring it to an end, and to promote justice and accountability.

Figure 3. Ten highest-risk countries not experiencing mass killing as of the end of 2022Back to top

Consistently high-risk countriesBack to top

In addition to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen, a few other countries have appeared near the top of our rankings for several years.

- Sudan (Rank: 4): Sudan has consistently ranked within the 15 highest-risk countries in our assessment. In April 2023, war broke out between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a militia group with ties to the Janjaweed, which targeted civilians in Darfur two decades ago. At least 5,000 people have been killed since the start of the conflict, and almost four million people have been displaced. The conflict shows no signs of abating. In the Darfur region, the RSF and its allied militias have deliberately attacked non-Arab civilians. The Museum issued a warning of the dire risk of genocide in Darfur in June 2023. Both the SAF and the RSF are accused of committing atrocity crimes against civilians. In addition, there are reports of widespread rape and sexual violence by the RSF. The Early Warning Project judged that there was an ongoing mass killing perpetrated by state security forces and associated militias against non-combatant civilians of non-Arab ethnic groups in Darfur as of the end of 2022; this risk assessment relates to the possibility of a new and distinct nonstate-led or state-led episode beginning, not to the ongoing episode continuing or increasing. Overall, the factors accounting most for Sudan’s current high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, the recent coup d’etat, and lower than average respect for religious freedom.

- India (Rank: 5): India has ranked in the top-15 highest-risk countries of our assessment for several years. Reports of targeted violence against ethnic and religious minorities have continued in 2023. The Hindu nationalist-led government has espoused hate speech against the country’s Muslim minority. Hindu-nationalist groups have engaged in anti-Muslim mob violence with impunity. Government authorities have repeatedly responded to these attacks by arresting Muslims and destroying Muslim property. Ahead of the general elections scheduled for 2024, some journalists have raised concerns about an increased risk of violence against Muslim communities. Attacks, including sexual violence targeting women and girls, against primarily Kuki ethnic communities in Manipur resulted in an estimated 160 people killed, over 300 injured, and thousands displaced by mid-August 2023. Additionally, Christian, Dalit, and Adivasi communities have faced targeted abuses. Government authorities have continued to crack down on civil society actors, including activists and journalists. According to our model, the factors accounting most for India’s high-risk estimate are its large population, and history of mass killing. The Early Warning Project judged there was an ongoing mass killing perpetrated by Naxalite-Maoists as of the end of 2022; this risk assessment relates to the possibility of a new and distinct nonstate-led or state-led episode beginning, not to the ongoing episode continuing or increasing.

- Ethiopia (Rank: 6): Ethiopia has consistently ranked within the top 15 of our assessment. Violent conflict is widespread, impacting multiple regions and civilians across the country. State-led mass killings against Tigrayan civilians and against Oromo civilians were both ongoing as of the end of 2022. The current risk assessment relates to the likelihood of a new mass killing, not the continuation or escalation of an ongoing one. Ethiopia’s high ranking indicates that the country continues to exhibit many characteristics common among countries that experience new mass killings. The Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) signed a cessation of hostilities agreement in November 2022, seemingly marking the end of one of the deadliest conflicts of the 21st century. The US government and the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia have stated that all parties to the conflict committed atrocities. Despite the peace agreement, violence has continued in Tigray, with recent reports of atrocity crimes, including conflict-related sexual violence. In the Amhara region, rising tension and recent clashes between Fano (an Amhara militia group) and the Ethiopian government have raised concerns for heightened violence. Additionally, ongoing conflict in the Oromia region, involving the Ethiopian government, Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), and Fano, has killed hundreds and shows no signs of resolution. Overall, the factors accounting most for Ethiopia’s current high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, large number of battle-related deaths (primarily armed conflict between the Government of Ethiopia, the TPLF, and the OLA), and large population.

What about cross border mass killing?Back to top

The Early Warning Project’s definition of mass killing excludes situations in which an armed group (state or nonstate) residing in one country attacks civilians in another country’s territory. The only exceptions to this rule are situations where we can document substantial and close coordination in killing operations between the foreign armed group and the government of the state where the targeted civilian group resides.

This means our definition of mass killing does not include Russian forces’ deliberate targeting of civilians in Ukraine, civilian killings in Yemen perpetrated by the Saudi-led coalition, or civilian killings in the war between Israel and Hamas.

The decision to exclude these mass killings does not involve a value judgment about the moral or practical significance of atrocities perpetrated during wars between states, international terrorism, and other international military operations, only a pragmatic judgment about what we are able to forecast more reliably.

Significant shifts in rankingBack to top

We highlight two countries that moved up and one that moved down in our rankings substantially between the 2022–23 and 2023–24 assessments.

- Tajikistan (Rank: 10): Tajikistan moved up considerably to the top ten highest-risk countries in our risk assessment for 2023-24. The shift can be most attributed to a recent increase in political killings approved or incited by top leaders of government. Government-led targeting against the Pamiri minority in the Gorno-Badakhshan autonomous region escalated in 2022. Authorities violently cracked down on civilians protesting against the discrimination and persecution of the Pamiri minority, reportedly killing at least 40 people in May 2022. The government has also targeted political opposition, religious communities, and human rights defenders, including through reported arrests and harassment. Human rights groups have documented apparent war crimes against civilians by Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan forces in the recent escalation in violence at the border between the two countries. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Tajikistan’s high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, that it experiences political killings, and its lower than average respect for religious freedom.

- Chad (Rank: 27): Chad has placed in our top 30 for several years running, but its ranking at 27th for 2023–24 represents its lowest ranking in several years, down from the top 5 in 2022–23. Chad’s lower ranking this year is mainly the result of a change in one variable: According to V-Dem, Chad did not exhibit inequality in levels of respect for civil liberties across different areas of the country in 2022, while it had in prior years. Having equal levels of respect for civil liberties across areas within a country (whatever the level of respect) is associated with a lower mass killing risk in our model. However, recent political turmoil and an apparent overall decline in respect for civil liberties in Chad suggests that it might not match this general pattern. Instability has beset the country since the 2021 death of its president of 30 years, Idriss Déby. In response, the military installed the late president's son, Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno, as interim president and head of a Transitional Military Council. The interim government violently repressed peaceful protests in October 2022 against its decision to extend the 18-month transitional period for an additional 24 months. Security forces killed dozens of people, while hundreds were reportedly wounded and arrested. Chad continues to experience risks for increased violence against civilians in several regions: extremist violence in the Lake Chad Basin, tensions between farmers and herders in the south, violence between armed groups at the border with Libya, and heightened instability in eastern Chad spurred by the conflict in Sudan. Déby has said he would allow for a return to civilian rule in the national elections scheduled for fall 2024; however, he has taken visible steps to consolidate power. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Chad’s high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing, that it experiences political killings, and that it experienced a coup attempt in the past five years (2021).

- Burkina Faso (Rank: 29): Burkina Faso moved into the top 30 highest-risk countries in our risk assessment, from the 40s in 2022–23. The shift can be most attributed to the coup in 2022 and increasing numbers of battle-related deaths. In recent years, the country has experienced growing instability and violence, including two coups in 2022. Since then, civilians have faced increased attacks by Islamist nonstate armed groups. More people were killed from extremist violence in Burkina Faso in 2022 than anywhere else in the world. Human rights groups have accused both government and nonstate forces of committing war crimes, notably murder and enforced disappearances of civilians. For example, members of the army allegedly targeted civilians in Karma village, killing at least 147 people in April 2023. The government has also recruited volunteer fighters on a massive scale to respond to increasing threats posed by nonstate armed groups. Conflict analysts warn that such mass mobilization could contribute to an escalation in state-led violence against civilians. Recently, President Traoré raised concerns of heightened instability when he hinted that the elections—slated to take place in 2024 to restore civilian rule—might be delayed. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Burkina Faso’s high-risk estimate are its recent history of coup attempts, presence of battle-related deaths (armed conflict between the Government of Burkina Faso, IS, and Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin), and high infant mortality rate.

Unexpected resultsBack to top

Global statistical risk assessments can help by identifying countries whose relatively high (or low) risk estimates surprise regional experts. In cases where our statistical results differ substantially from expectations, we recommend conducting deeper analysis and revisiting assumptions. The purpose of this analysis is not to pit qualitative analysts and statistical models against one another but rather to deepen our understanding of risk in the country in question. We highlight two countries that, in our informal judgment, fall into this category.

- Indonesia (Rank: 14): Indonesia’s high ranking of 14th may come as a surprise given that it is one of the world’s largest democracies and that it plays a major political role on the international stage. Nevertheless, Indonesia has consistently ranked as high-risk in our assessments. Indonesian state security forces often use excessive force against civilians, the media, and civil society groups. Authorities have consistently resorted to force to disband peaceful protests, seen during the 2021 anti-racism demonstrations in Indonesia's Papua and West Papua provinces, where political tensions run high. In recent years, armed conflict has increased between Indigenous Papuan supporters of Papua’s long-standing independence movement and the Indonesian government. The Museum’s Early Warning Project published a report in July 2022 assessing the risks of mass atrocities in the Papua region. According to our model, the factors accounting most for Indonesia’s high-risk estimate are its history of mass killing and large population.

- South Sudan (Rank: 86): Despite ongoing violent conflict, human rights abuses, and a severe humanitarian crisis, South Sudan ranks 86th in our assessment for 2023–24. The Early Warning Project already considers there to be two mass killing episodes—one state-led and one nonstate-led—ongoing in South Sudan since 2013. The current risk assessment relates to the possibility of a new and distinct nonstate-led or state-led episode beginning, not to the ongoing episodes continuing or increasing. While the 2018 ceasefire appears to be holding, instability has persisted. The Museum continues to draw attention to the worsening risk of mass atrocities, releasing a brief earlier this year underlying dynamics of concern. The UN has warned that the recent outbreak of conflict in neighboring Sudan might escalate regional instability and further jeopardize South Sudan's peace process. Looking ahead, South Sudan’s first-ever and long-delayed elections scheduled for December 2024 should be closely monitored amid warnings of future conflict. A detailed qualitative assessment is necessary to help understand the nature and severity of atrocity risks, whether they be from escalation of an ongoing episode or the start of a new episode.

Exploring changes to a country’s risk factors: The example of SudanBack to top

The data used to produce this assessment are from 2022 (published by most sources in early- to mid-2023). This means that changes that occurred in 2023 are not captured in this risk assessment. To enable users to examine how such changes might affect a country’s risk estimate and ranking, our online platform has an interactive data tool. The tool allows users to explore how changes to a country’s risk factors would affect its risk of mass killing, holding all other variables constant. Users may want to:

(1) See what a country’s risk and ranking would be if we were to observe some different set of values on its risk factors (e.g., though no war broke out and battle deaths were zero, what if we instead saw a large number of battle deaths?)

(2) Manually update country risk based on known changes (e.g., knowing that a coup occurred in a country, users can see how a change in that variable would affect the risk and ranking)

(3) Adjust risk factor values where users disagree with a data source’s coding judgments

For example, in 2023–24, Sudan ranks 4th, with a 5.7 percent estimated risk, or a one in 18 chance of a new mass killing. This assessment is based on 2022 data. However, someone following events in Sudan may suspect that events over the course of 2023—namely, the outbreak of war on April 15—may impact that risk.

Using the tool, we see, for example, that if political killings were to become systematic and incited or approved by top government leaders, Sudan would rank 1st and its new risk estimate would go up to 10 percent, or about a one in 10 chance of a new mass killing.

ConclusionBack to top

Early warning is a crucial element of effective atrocity prevention. The purpose of our statistical risk assessment is to provide one practical tool to the public for assessing risk in countries worldwide. This tool should enable policy makers, civil society, and other analysts to focus attention and resources on countries at highest risk, especially those not currently receiving sufficient attention.

This quantitative assessment is designed to serve as a starting point for additional analysis. Governments and international organizations have developed and implemented tools for qualitative atrocity risk assessments. We see the application of such tools as a complementary next step after our statistical analysis. These in-depth assessments should in turn spur necessary adjustments in strategic plans, budgets, programs, and diplomatic strategies toward high-risk countries. By combining these approaches—global risk assessment, in-depth country analysis, and preventive policy planning—we have the best chance of preventing future mass atrocities.